There is a new home going up right outside my window. All day long I hear the clamor of construction – pneumatic hammers, back-up beeps and rock blasting equipment. Some days I’m happy to start the dishwasher just to balance out the cacophony of noises. The other day, right around dusk, I sensed something was different. I realized that the neighborhood was quiet. Every motor and power tool was turned off. I looked out and saw the silhouettes of the construction crew against the greying sky. They moved around like dancers – graceful and fluid. They strode across the roof beam as if they were on solid ground. I started to get a zen-like feeling as I watched them conduct their final tasks for the day, appearing to have no concern over the fading light, almost as if they didn’t need it. And then it dawned on me: I was watching “unconscious competence” in action.

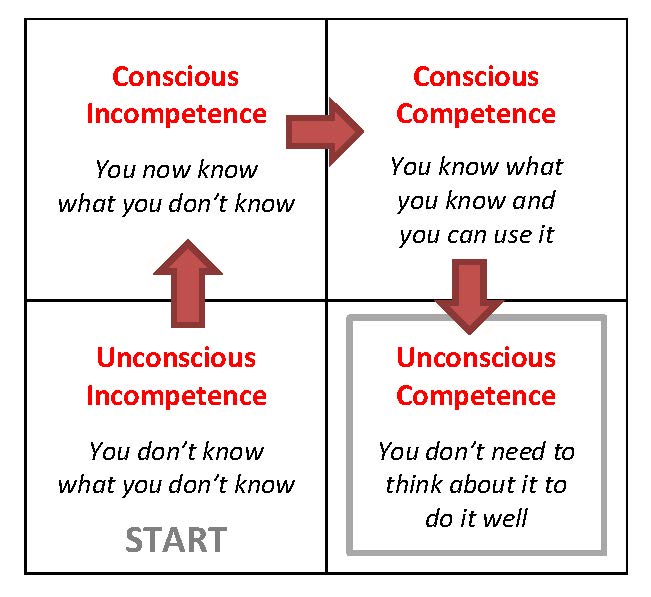

Unconscious competence is the final phase of Noel Burch’s Four Stages of Competence (see side bar). People who are unconsciously competent are so skilled in a particular task that they no longer have to think about it. It’s a worthy aim for any practitioner, but no one can achieve that phase without hard work, feedback, and a commitment to one’s craft. In his book Outliers, Malcolm Gladwell offers another criteria for reaching this end state of effortless excellence: 10,000 hours of practice. We all have to progress through the first three stages to reach the point at which things become second nature.

Unconscious competence is the final phase of Noel Burch’s Four Stages of Competence (see side bar). People who are unconsciously competent are so skilled in a particular task that they no longer have to think about it. It’s a worthy aim for any practitioner, but no one can achieve that phase without hard work, feedback, and a commitment to one’s craft. In his book Outliers, Malcolm Gladwell offers another criteria for reaching this end state of effortless excellence: 10,000 hours of practice. We all have to progress through the first three stages to reach the point at which things become second nature.

In our presentation coaching, we often find that our clients have some core gift or skill that they have overlooked in their quest to develop another skill. We try to point out these unconsciously competent aspects in their speaking repertoire so that these skills can be called upon when it’s time to stand and deliver. Some people have a way with words. Others have a great sense of humor. One recent client had expert knowledge in a highly-sought after sales technique, but he was so focused on his inability to use his hands effectively that he completely undermined his greatest gift.

As we have said before, most audiences will forgive a few ums, a little swaying, and bouncing hands if the speaker is confident and offers something of value. If the audience learns something or leaves feeling motivated or inspired, then most bad habits will be forgotten. It’s time to take a mental inventory of your strengths and your unique gifts and bring them back into the rotation. Unconscious competence is not a permanent state. Even the most gifted practitioner must refresh and renew their skills. Otherwise, unconscious competence turns into complacency.

– Barbara